A Ramadan of violence and loss

The war in Gaza has cast a pall over the Islamic holy month of Ramadan, a time of fasting and community. For Palestinians in the West Bank and East Jerusalem, the occasion is always bittersweet, marked by moments of joy and constant reminders of the Israeli occupation that shapes their lives. Celebrations are circumscribed by Israeli restrictions. Families navigate checkpoints to gather for meals. Violence can interrupt prayer or play at any moment.

Jerusalem’s al-Aqsa Mosque compound, and the golden-domed shrine at its center, sit on a site known to Muslims as the Noble Sanctuary and to Jews as the Temple Mount. The site is sacred to both groups. It has been a frequent flash point in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

During Ramadan, hundreds of thousands of Palestinians typically gather at the site, from where they believe the prophet Muhammad ascended to heaven. Jewish worshipers escorted by Israeli police sometimes also pray near the Dome of the Rock, a site that is in theory only reserved for muslim worshippers and a move that have sparked violence in the past.

In the hour before iftar, the post-sunset meal, last-minute shoppers hurried around the streets of Jerusalem’s Old City, picking up bread, juice, and desserts. A hush settled over the cobblestones at sunset, as families headed homeward to break their fasts together. Afterward, a stream of people surged toward al-Aqsa for Taraweeh, the nightly Ramadan prayer. But the scene is relatively muted compared with most previous years.

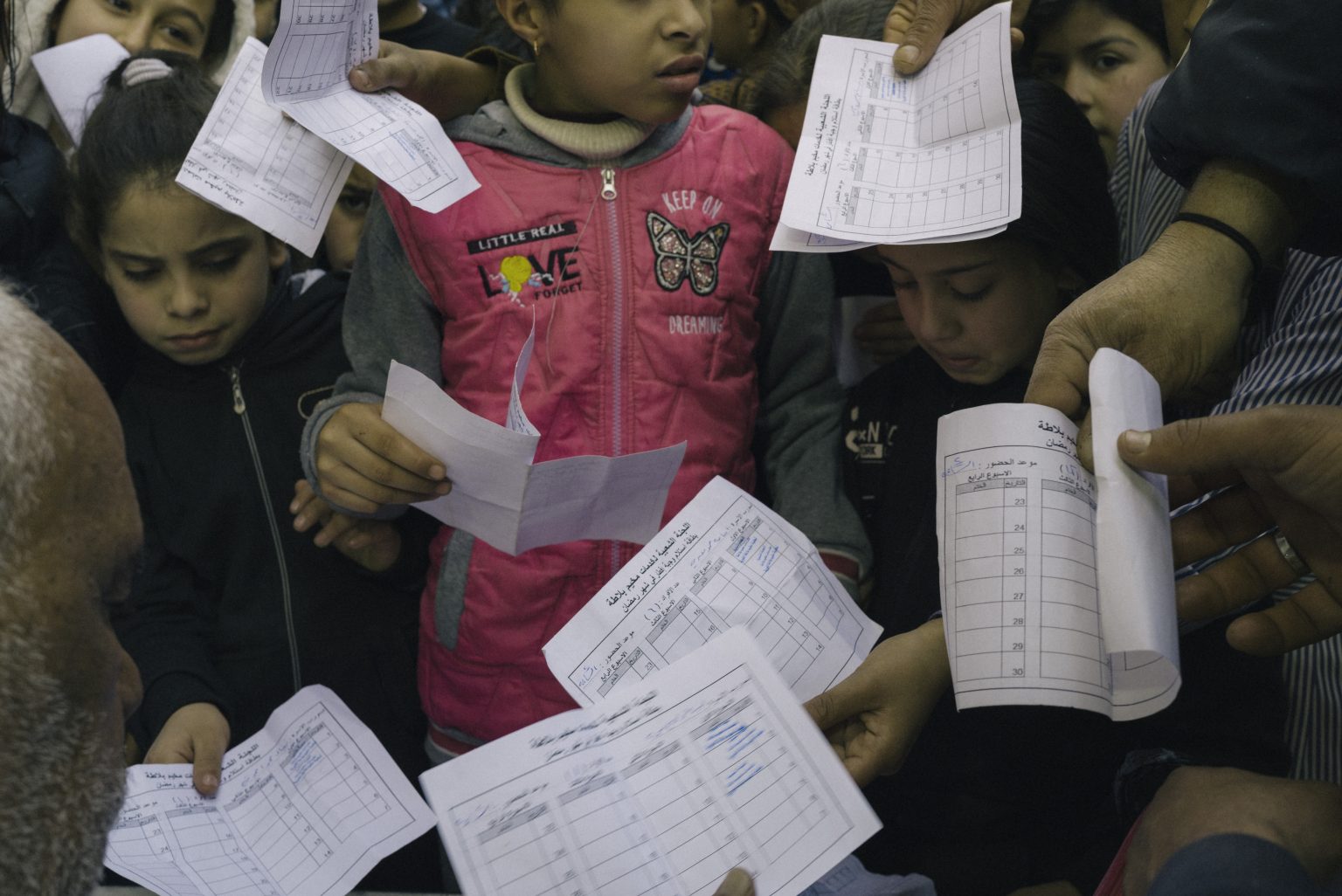

On Tuesday, March 12, celebrations in Jerusalem were marred by the killing of a 12-year-old boy by Israeli border police in the Shuafat refugee camp, on the city’s edge.

Ramy Hamdan al-Halhouli, had gone with friends after the nightly prayer to the road behind his house to light fireworks, a common Ramadan pastime. As reports of the shooting circulated, Israeli Police said in a statement that the “suspect” had endangered its forces.

The northern West Bank city of Nablus is at once a commercial hub and a hotbed of Palestinian militancy. New Israeli restrictions since Oct. 7 are crippling the economy. Many Nablus residents are out of work and struggling financially. Israeli military raids here have become more frequent and violent since Oct. 7, families say. Mothers stay awake at night, fearing that their sons will be arrested or killed.

This Ramadan is the first that Fares Samamreh, a Palestinian farmer and father of 18, has spent away from the land that he worked all his life in a village near the Palestinian town of Hebron. Settlers descended on the family’s home at night, threatening them and flying drones that scared their livestock. The men carried guns and wore army uniforms to appear more menacing.

On Oct. 28, fear drove the Samamrehs to pack up their belongings and leave, becoming one of more than 150 families “forcibly transferred” by settlers and soldiers from rural communities in the West Bank since the war began.